Laura Kipnis and Jennifer Doyle Explain It All To You……

By Lisa Duggan

In 2013 I read a stunning short article on the notorious Steubenville rape case by Joann Wypiejewski in The Nation, “Primitive Heterosexuality: From Steubenville to the Marriage Altar,” with the subtitle “Straight culture teaches its children that sex is either of the jungle or the picket fence.” Wypiejewski rejected the stark melodramatic terms of reigning descriptions of “rape culture” to place sexual assault on a spectrum with the normative coercions and inequalities of heterosexual courtship. She then took an extra breathtaking step to indict the supposedly adult model of ideal marriage that ends courtship as the site for the very abuses assigned to “rape culture.” She closed by looking not to the expansion of marriage to same sex couples, but to queer sexual cultures for models of sexual ethics:

Frankly, heteros have nothing to teach homos beyond, maybe, how to endure childbirth. If the zeal to arrest toddlers for stealing a kiss and to lock away teenagers for having stupid, drunken, nasty sex is an indication, the lesson ends once the babe is through the birth canal. The opposite—that heteros have something to learn, from the history of gay liberation rather than marriage equality—is surely true.

This is not to romanticize homosexuality. Regardless of the subjects, sex is a mix of rapture and risk, sweetness and cruelty or something more humdrum. But because history did not present gay people with the open choice of the jungle or the picket fence, they developed an alternative culture, a relational language and set of ethics not just to avoid a trap but to have at least a decent experiment, a decent anonymous encounter, a decent first time—not necessarily a transcendent one (though maybe), but not an awful one—and a different sense of family. Gay kids may drink or damage themselves and others for all the reasons anyone in this society might and more, but gay culture doesn’t teach its kids that the surest route to sex is through a bottle and a lie. Straight culture teaches that.

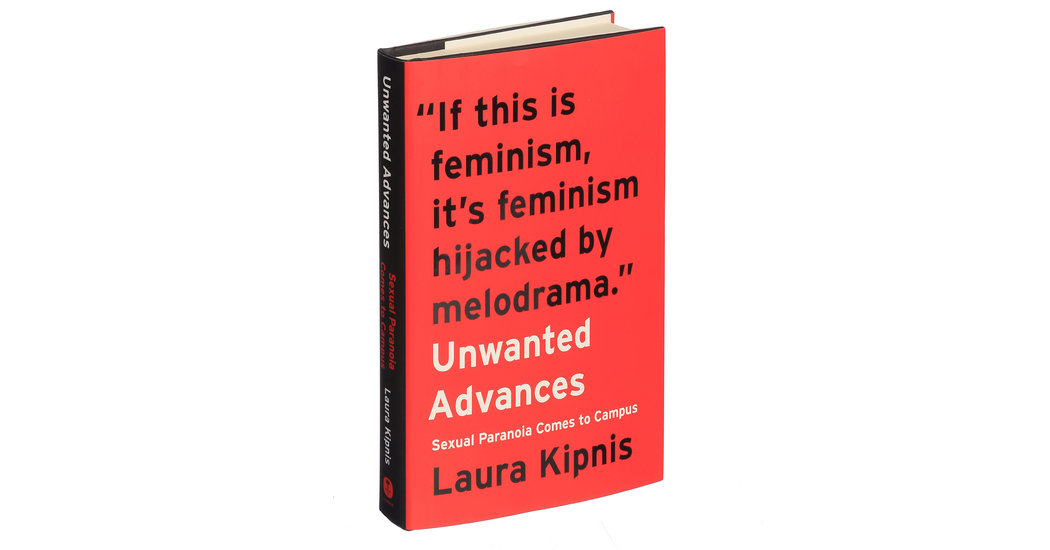

So OK, maybe Wypiejewski romanticizes gay culture a wee bit, forgivable for a straight lefty feminist with a galvanizing point to make. She is also elaborating the point of Douglas Crimp’s famous defense of queer “promiscuity” as a resource rather than a scourge in the midst of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. In the current continuation of the various crises over sexual assault, Laura Kipnis has weighed in with a book that shares some of Wypiejewski’s points, but misses others. Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus (Harper Collins 2017) sounds a crucial, complacency piercing alarm about the way Title IX investigations of sexual assault on campus have veered widely afar from the goal of fighting gender inequality (as Title IX was designed to do when added to the Higher Education Act in 1972) to become an underground wave of secret tribunals with inconsistent and unaccountable rules and outcomes.

I think Kipnis is largely correct about what has happened since Title IX’s purview was expanded to cover sexual assault in 2011. Though the confidentiality rules prevent any of us from really knowing much, Kipnis makes illuminating use of a rare breach in that imposed silence—a cache of documents released by accused Northwestern professor Peter Ludlow, who left his tenured philosophy position midway through his “trial” without any confidentiality agreement. My own academic network confirms the widespread existence of Kafkaesque “investigations” in which “targets” are not given clear accounts of charges or allowed to defend themselves, in just the ways Kipnis describes via the Ludlow investigations. My informants are disproportionately queer studies scholars, far too many of whom are charged with sexual misconduct (which can include teaching “improper” materials in class) by unstable, closeted or homophobic students. Campus activists against sexual assault routinely ignore this dynamic and many others when they call on us all to simply “believe the students,” the current variation of “believe the women” and “believe the children.” Activist support for administrative procedures that empower accusers (too often simply referred to as “survivors,” a problematic slippage) without question, while minimizing the rights of the accused, is utterly wrongheaded and misguided. These activists do not imagine themselves in the role of accused “target,” but they should, they must. To imagine oneself as possibly accused rather than only as accuser can illuminate the stark imbalances at the core of current practices of investigation and adjudication. And this is one of Kipnis’ major points—empowering the administration to act under cover of confidentiality removes mechanisms of accountability. This is a dangerous path.

Unwanted Advances also makes a key point repeatedly: Narratives of endangered young women bent to the will of powerful male professors (even in the absence of any supervisory role) are not feminist. These melodramatic rescue narratives offer a hero’s role to administrators, who overreach in an old story of young women without agency violated and rescued. This is the territory of “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,” the lynching narrative, the progressive era “white slavery” panic. Kipnis points out that efforts to educate young women about how to understand their milieu and defend themselves are too often interpreted as “blaming the victim.” Campus activists would do well to read feminist history and critically examine the emergence of what sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein has named “carceral feminism” and legal theorist Janet Halley has called “governance feminism”—political formations featuring a turn to often punitive state and administrative “solutions,” rather than organizing to address and transform social relations.

But here we begin to reach the limits of Kipnis’ book. The history of feminism that she provides actively erases larger framing contexts that are crucial to the dynamics the author wants to analyze. The story of the emergence of “sexual harassment” as an innovative feminist concept, eventually converted by corporations and university administrations into a military style anti-fraternization policy policed by liability lawyers and elaborated by paid consultants, is mostly missing as the important background to the current spread of Title IX investigations. In the world off campus the context of the feminist “sex wars,” the debates over sex work and sex trafficking, and the horrific years of the “Satanic” child sexual abuse panic in the 1980s, are barely mentioned. Kipnis takes the vocabulary and arguments of these earlier fights (the sex wars discussions of “pleasure vs. danger” and the debates about female sexual agency especially), but rarely credits them.

This narrow framing is symptomatic of the reversed melodrama at the center of Kipnis’ narrative, a frame that features the author in both the victim’s and hero’s role. She was the “target” of a Title IX investigation for an earlier article (and is currently being sued by one of the students she writes about in the book), and in response represents herself as fighting the good fight for free speech and sexual agency. In her book she rarely shares that heroic spotlight with historical or current figures. She likes to pose as the badass, throwing around provocative claims and standing up for those stricken silent by confidentiality rules.

This pose with its narrowing effect becomes especially clear when Unwanted Advances is read alongside Jennifer Doyle’s 2015 book, Campus Sex, Campus Security (Semiotext(e), 2015). Doyle was also involved in a Title IX case that did not go her way, but this experience does not center the analysis of the book. Doyle uses the “problem” of off the rails administrative procedures to widen her vision and take in the precarious state of “the campus” at this moment in neoliberal time. Drawing on the 2011 ‘incident” of campus police pepper spraying non-violent motionless students at the University of California Davis, Doyle makes a series of astute and revelatory connections between campus security and sexual politics through a series of short, staccato chapters filled with quotable insights. At UCD, the Chancellor worried that “non-affiliates” from Oakland (read young black men) would take advantage of “very young girls” on campus and put the university “in violation” of Title IX. From there Doyle looks at race and colonial legacies, the insecurity of students with high tuition and faculty with part time appointments, and the experiences of queer and racialized students and faculty under campus security regimes—considering the Penn State/Jerry Sandusky scandal, the suicide of Tyler Clemeni at Rutgers, the Rolling Stone story of a gang rape later revealed as a hoax at the University of Virginia, the violent arrest of Prof. Ersula Ore for jaywalking at Arizona State, and more.

The point of Doyle’s analysis across all these instances is that the university finds itself vulnerable, positions itself as threatened, and deploys ramped up risk management and security measures for self-defense. In the Title IX cases the university is defending itself from being “in violation” and losing money, not protecting the “very young girls” who are imagined as the ideal accusers, without agency of their own. This comparative framing makes the exclusion of political economic context, and of critical race and queer theory, from Kipnis’ text very clear. Kipnis “includes” race and queer sexuality with a few random comments, one example involving black athletes (where the word “packs” is used), and a few same sex examples that are unintegrated into the analysis. Doyle’s book shows readers what it means to bring these analytic frames together, rather than just use add on unanalyzed examples.

But Doyle does slip into the insupportable “believe the women” posture occasionally. In concluding her account of the Rolling Stone rape hoax story of 2015, written by Sabrina Rubin Erdely based on the unchecked facts of an unnamed accuser, she comments “Who cares, really, about what women say? For that matters, who cares about what women write?” (p.21) Um, what? Doyle twists herself into a pretzel trying to avoid criticizing either the accuser or the writer, instead going for the magazine’s staff. It’s a stretch, based on a melodrama of female innocence and male perfidy that she otherwise avoids.

This slip, and others like it, serve to illustrate how pervasive and apparently irresistible conventional sexual melodrama can be, all across the political spectrum. Though Kipnis is countering the melodrama of gendered sexual danger that frames the recent deluge of Title IX tribunals, she fails to note that this story is itself a reversal of another pervasive melodramatic tale—in which innocent men’s lives are ruined by scheming women. The tide of Title IX complaints is in part a justifiable effort to attack the assumptions that supported widespread dismissal of women’s accusations against serial harassers and attackers, who were often protected by administrators in the pre-Title IX era. The rage and frustration generated by decades of such dismissals in part fuel the relentless hostility to “targets” expressed by too many Title IX officers. Now Kipnis counters the counter narrative, with an again reversed tale of scheming women and falsely accused men. Though she acknowledges that this is not the whole story, that sexual assault on campus is real, and that harassers and rapists are sometimes excused and protected, these admissions are throwaway sentences that pop up now and then in the body of a text utterly devoted to a highly gendered melodrama featuring manipulative female accusers and vindictive unaccountable bureaucrats, versus men whose lives are unfairly ruined.

There is a moment in Unwanted Advances when Kipnis reports the events of one of her central cases to a psychiatrist friend, and recounts his speculative diagnoses for one of the young women accusers—borderline or hysterical personality disorder (p. 74). Arguably, this kind of third hand psychologizing crosses a line from hard hitting but illuminating critical analysis to personal invasion. Does this move justify my own speculation that Kipnis may have some unresolved oepidal issues? A father she wants to rescue from a controlling, scheming mother? Just guessing!

Ultimately, both Kipnis and Doyle, like Wypiejewski, want to replace the sensational, melodramatic tales of sexual danger with detraumatizing strategies for thinking about sexual assault (which would involve reducing the demand for anonymity and confidentiality, strategies that only reinforce stigma, and in the context of Title IX, prevent accountability). Doyle specifically calls for placing rape on a spectrum of normative sexual coercions including state regulated marriage and reproduction, while Kipnis points to the need to address “the learned compliance of heterosexual femininity.” Kipnis further calls for assertiveness training and self-defense—student initiated strategies for challenging male aggression. Why not organize, act up, create new contexts for social and classroom life, rather than call endlessly for more and better administrative procedures? Both books emphasize the danger of empowering administrators this way—and surely the example of the administrative persecution of Palestinian students and professors should show us that danger in action. Most broadly, it is the clear implication of Doyle’s book that organizing strategies need to reach beyond inequalities of gender and sexuality to address the context for them, in the political economic context of risk management and global securitization.

10 replies on “Rapture and Risk on Campus in the Age of the Sexual Security State”

[…] and Jennifer Doyle’s books on Title IX and campus sexual assault and harassment in a Bully Bloggers post. There is a lot going on in this post—some of which I agree with, but much of which I disagree […]

Very interesting unsigned critique on ofqueerbeing.wordpress.com. Too much to respond to here, but two responses: (1) I was not referring to *all* students complaints as invalid, at all, and (2) I was not meaning to reference mental illness per se with the work “unstable,” I meant to reference the kind of projection that occurs when students with queer feelings try to squash them, as in Edmund White’s “A Boy’s Own Story.” Sadly, such students make charges of sexual harassment and misconduct with some regularity, as well as file complaints based on queer course content. We don’t know how often because of “confidentiality.” It is a terrible terrible mistake to simply “believe” such students when they say they have been harmed. In fact, it is a disservice to them as well as their “targets” to do so.

Hi,

I apologize for having not signed the post–I threw together the blog hastily. It wasn’t an attempt to hide behind internet anonymity. I’ve happily outed myself now as Joseph Gamble, a PhD candidate in Women’s Studies and English at the University of Michigan. The post has been edited to make this more clear.

I agree, of course, that some students might complain in a way that is, to my mind, inappropriate about sexual–and especially queer–content in a course. But I do feel quite uncomfortable with projecting some resistance to queer feeling onto these plaintiffs, even as (you’re right) resistance to queer feeling might be precisely what’s driving them to complain. I would hope, though, that whichever adminstrators might be involved in that complaint–chairs, deans, ombuds people or, god forbid, provosts–would have the clarity and backbone necessary to stand up for the faculty member in such cases (as happened several years ago, for instance, with the kerfuffle over David Halperin’s “How to Be Gay” course in my own department).

I agree that it would be a disservice to both the student and, especially, the faculty member to take punitive action based on such a complaint, but I’m not sure that that means that we shouldn’t take the complaint “seriously,” if that distinction has any difference in it. (And I really do feel this personally: I’ve decided to not teach several pieces of early modern pornography in my “Renaissance Sexualities” course precisely because I worry about potential for very negative student reaction).

But perhaps I am being naive about university administration.

I do have to say, though, that whether or not you meant to reference mental illness with the word “unstable,” it pretty clearly has that referent, no? What you describe above as your intent seems to me to be a description of the conceptual/rhetorical work that the word “closeted” is doing, but it feels to me as if there’s a pretty spacious conceptual leap from “unstable” to “the kind of projection that occurs when students with queer feelings try to squash them,” even when “unstable” is cozying up next to “closeted.”

I do hope you’ll forgive (or revel in?) the queer snark of my post, which I’ve learned largely from you and the other bloggers here.

Best,

Joey

Thanks for identifying yourself and for this response. I don’t think the administrative process of complaint allows for any nuance or flexibility, unfortunately. I personally know queer faculty who have been charged and fired based on very ridiculous complaints. And I also think there is a difference between closeted and projecting in an “unstable” way. It is also possible to deal seriously with students without taking all their complaints into the horrendous process of unaccountable prosecution that is the Title IX investigation.

I’m sorry you stopped teaching materials because of student sensitivities. Would you stop teaching queer materials completely because of conservative Christian students’ claims to be offended and harmed by them?

No need to reply…. Just rhetorical questions.

LD

I’m a bit disturbed, though, by Kipnis’ claim that “single non-hideous men with good jobs (or, in this case, an international reputation and not without charm) don’t have to work that hard to get women to go to bed with them in our century.” This post does some of the work of checking Kipnis for her endorsement of the “decent man whose reputation is besmirched by a crazy woman” melodrama, but I really wish more reviewers would take her to task for, in a way, becoming another Camille Paglia, at least at points. Really? Powerful men have no incentive to commit sexual harassment or assault?

(Wonderful synthesis and critique, in any case!)

I agree about that quote! Really reactionary …

Reblogged this on El diario de la adultez.

[…] The problems with Unwanted Advances have been addressed by the philosopher Jonathan Ichikawa and a few others. There are so many differences between our books — I think the only thing we have in […]

[…] There are lots of outraged critiques of Kipnis’s book out there, and they’re as worthy of consideration as the book itself. Of all the reviews and critiques I have read of Unwanted Advances, this thoughtful review by Lisa Duggan stood out for me as particularly sharp, fair, and useful: “Rapture and Risk on Campus in the Age of the Sexual Security State.” […]

[…] a trend she notes cannot be substantiated in the absence of publicly available data, though other scholars have also written about this in the public […]