Peter Coviello is the author of four books, including Tomorrow’s Parties, Long Players: A Love Story in Eighteen Songs, and, most recently, Make Yourselves Gods: Mormons and the Unfinished Business of American Secularism. He is Professor of English at UIC, and he lives in Chicago.

It’s been a big media week for many-decades-departed French intellectual historians. Michel Foucault – whom some of you may remember from a graduate course you took in 1994 – found himself name-checked, on the Op-Ed pages no less, in a pair of major English-language dailies. As protests in the wake of the police murder of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd convulsed not just the United States but the planet, as a pandemic continued its awful decimating work, as the possibility of an unprecedented economic contraction loomed evermore asteroid-like in the night skies of even the most Panglossian market forecasters, and as temperatures tipped up past 100 degrees in the Arctic Circle, a couple of Professional Opinion Havers paused amid their reflections to invoke the author of such chart-toppers as The Archeology of Knowledge and “Theatricum Philosophicum.” As one friend observed, “2020 does not quit.”

The redoutable David Brooks, in a mea-culpaish column from 18 June entitled “How Moderates Failed Black America,” noted in passing that conservatives like to blame spasms of dissent on the intellectual foment brewed up by “campus culture,” which he then described with enviable concision: “People read Foucault,” he wrote, “and develop an alienated view of the world.” And then, on 19 June, in Rupert Murdoch’s venerable daily The Australian, Adam Creighton came out of the gate harder still: “Want to spent [sic] three years reading Foucault and dreaming about vandalising Captain Cook statues?” he wrote, with the squeaking pugnacity proper to austerity economists everywhere. “Fine, but don’t expect a cent from taxpayers.” (This line afforded the piece its deathless title: “Want to study Foucault? Don’t expect a cent.”) High theory as such may be back on its heels, and something of the 90s luster may indeed have faded from the project of genealogical critique. And yet there is apparently no gainsaying the mystically aversive power that our man Foucault continues to wield – more than a third of a century after his death – upon the planet’s burbling reactionaries.

The redoutable David Brooks, in a mea-culpaish column from 18 June entitled “How Moderates Failed Black America,” noted in passing that conservatives like to blame spasms of dissent on the intellectual foment brewed up by “campus culture,” which he then described with enviable concision: “People read Foucault,” he wrote, “and develop an alienated view of the world.” And then, on 19 June, in Rupert Murdoch’s venerable daily The Australian, Adam Creighton came out of the gate harder still: “Want to spent [sic] three years reading Foucault and dreaming about vandalising Captain Cook statues?” he wrote, with the squeaking pugnacity proper to austerity economists everywhere. “Fine, but don’t expect a cent from taxpayers.” (This line afforded the piece its deathless title: “Want to study Foucault? Don’t expect a cent.”) High theory as such may be back on its heels, and something of the 90s luster may indeed have faded from the project of genealogical critique. And yet there is apparently no gainsaying the mystically aversive power that our man Foucault continues to wield – more than a third of a century after his death – upon the planet’s burbling reactionaries.

It’s a mug’s game to venture too earnestly into the cobwebbed psychic recesses of the world’s rightist punditry. As here, however, the temptation to do so is often great, and I think you can see why. One need not be fluent in the byways of Lacanian psychoanalysis to see a certain, oh, symptomaticity at work. Were you a person paid to speak for and to those who, with a vague but vituperous nostalgia, cherish the allegedly commonsensical status quo, Foucault might well be a target difficult to resist. There he stands – gay, bald, French – discarding the holy verities with provoking panache and savoir-vivre. Possessing something of the risible-yet-menacing obscurity of Derrida, though spiced with a nearer proximity to the heat of insurrectionary politics – memories of ’68 and all that – “Foucault” offers a ready metonym for what writers only marginally lazier than Brooks and Creighton derisively call “postmodernism” or “deconstruction,” though among the more blithely antisemitic the term of art continues to be “cultural Marxism.” Foucault: as malign incantations go, meant to summon up the dread permissive power of antifoundational speculation and Gallic attitudinizing, it will serve.

It’s a mug’s game to venture too earnestly into the cobwebbed psychic recesses of the world’s rightist punditry. As here, however, the temptation to do so is often great, and I think you can see why. One need not be fluent in the byways of Lacanian psychoanalysis to see a certain, oh, symptomaticity at work. Were you a person paid to speak for and to those who, with a vague but vituperous nostalgia, cherish the allegedly commonsensical status quo, Foucault might well be a target difficult to resist. There he stands – gay, bald, French – discarding the holy verities with provoking panache and savoir-vivre. Possessing something of the risible-yet-menacing obscurity of Derrida, though spiced with a nearer proximity to the heat of insurrectionary politics – memories of ’68 and all that – “Foucault” offers a ready metonym for what writers only marginally lazier than Brooks and Creighton derisively call “postmodernism” or “deconstruction,” though among the more blithely antisemitic the term of art continues to be “cultural Marxism.” Foucault: as malign incantations go, meant to summon up the dread permissive power of antifoundational speculation and Gallic attitudinizing, it will serve.

What, along these lines, could be more pithily perfect than Brooks’s lament? People read Foucault – yes, go on – and develop an alienated view of the world. It is a compacted little scene of seduction, rendered with exactly the dopey sweater-vest unsexiness you’d hope for from a David Brooks column. No need, here, for teachers, or for the laggardly efforts of reflection, or for that matter for any near experience of the liberal world’s uncountable varieties of incentivizing rationality, managerial coercion, disavowed violence, oh no. On this model, the circuit runs, with an impressively instrumental immediacy, from text to consciousness to statue-toppling political resolve. I wish for all my fellow professors seminars that run so smoothly.

It all inclines toward the ludicrous, certainly – the roster of genuinely incendiary authors you might name before landing upon Foucault is, in the first place, very very long – but I’ll give credit where it’s due. Neither Brooks nor Creighton seem to have in mind Foucault’s work on policing, or the wedding of hyper-economized political life to regimes of security; they are not thinking, so far as I can tell, about his writings on control societies, the carceral state, the management of populations as aggregated into racialized subgroupings, differently exposed to quantums of opportunity, protection, violence, death. But they are, in their way, getting something right about Foucault’s project. For it is indeed among his ambitions to suggest that there is an outside to the empire of liberalism, and its many self-sanctioning rationalities. In his interest in the volatile interplay between that unconverted outside and the forces that seize and make it knowable, and in his altogether cold regard for the narrowed horizons of an emancipatory liberalism, he takes his place within a long and vital dissident philosophical tradition that runs from Marx and Nietzsche out to DuBois, Fanon, Wynter, Spivak, Spillers, and many another. And this, among the pundit class, does not sit well.

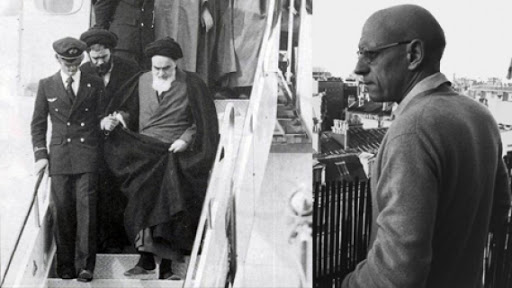

Nor has it done, for some time. In his excellent book from 2016, Foucault in Iran, Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi reminds us that, for a certain style of critic reenergized by what he aptly calls “the civilizational ardor of the post-9/11 moment,” Foucault stood out as a villain among villains. In his essays on the Iranian Revolution in particular, he committed a capital crime, which for these critics was a failure, prevalent among “poststructuralists” generally but led by Foucault, “to reckon with the catastrophic consequences of deviating from the project of the Enlightenment.” To have shown a sympathetic interest in the Iranian Revolution – to have been “kindled by witnessing a moment of making history outside the purview of a Western teleological schema” and to have written in resistance to “bifurcated conceptions of Islamist versus secular politics based on a temporal map of Enlightenment rationalities” – is, for critics of this sort, as good as to have cheered on the hijackers. Echoes of this civilizational horror are there to be heard in today’s aghast invocations, though for our part we might hear too a different set of ironies. How after all does one assess that “civilizational ardor” in the context of 2020, what with “growth” fetishism giving inexorable way to impending economic and environmental collapse, fascoid populisms rising vertiginously, and the creaking edifice of post-War liberal-imperial consensus looking more and more ready to topple? The murder’s call, we might say, has always been coming from inside the house.

Now, I do not mean to suggest that, since reactionaries say his work is malignant and galvanizing, it therefore follows that Foucault must be regarded as indispensable to any left-oriented or liberationist intellectual project unfolding in the present tense. I find him greatly enabling, it’s true – of which more in a moment – but god knows that’s not because I imagine his is the key that fits all locks. His use to you will depend, as with most theorists, on the questions you wish to ask, as well as your orientation toward them. It’s not hard to imagine an interest in, say, police power that might be better served by reading George Jackson, or Angela Davis, or Ruth Wilson Gilmore – which is not, at least to me, a dismissal of the work of Discipline and Punish.

And anyway, such disclaimers as these are perhaps by now unnecessary, inasmuch as a more left-oriented critique of Foucault is at this point fairly well-established. In the meme-ified way of contemporary things, these critiques have acquired, some of them, a certain ready-to-hand familiarity. For those opposed to what is called “identity politics,” often as linked to the 90s-style queer theorists most identified with works like The History of Sexuality, Foucault stands in for a reduction of the sphere of the political to the realm of the subject, as she or they or he has been “constructed” or “discursively constituted,” and a drawing-away from the cross-identitarian solidarities that make for mass movements. Then, too, are the related and frequently recurring online inquiries – Foucault: WAS HE A NEOLIBERAL? – that bloom and wither like annuals, and tend to be about as tedious, as italicized by undergraduate tendentiousness, as you’d guess. (If you insisted that Jacobin had published some eight or nine of these in the last half-dozen years, each with the identical thesis, I could not find it in my heart to fact-check you.)

A more recent and more interesting version of the critique identifies “biopolitics” with its use in the context of New Materialism, and so with a thoroughgoing vaporization of the realities of capitalist political economy in the constitution of life, such as might be found in, for instance, the work of Bruno Latour. This latter turn, for me, amounts to a wholly salutary refusal of Latour (in that it follows Jordy Rosenberg’s damning critique, from 2014, in “The Molecularization of Sexuality”) that is also, much like the line on identitarianism and the subject, of equivocal value for thinking about Foucault’s work, rather than its holographic appearance in the recountings of his less agile admirers. Latour, after all, represents Foucault’s project with about the acuity that Marx’s is exemplified by, say, Zizek.

These assessments may be more and less acute – as I say, they vary – but again that’s not because there is nothing to be said about the relation between biopolitics and political economy, governmentality and empire, security and the circuits of capital. There very much is. Foucault’s work persistently lays a certain kind of stress on the questions he takes up, often in the effort to shake them free of their embeddedness in what he takes to be the more rote traditions of Marxist analysis proper to pre-68 France. That, along with the habitual tuning of his own style of critique toward layered irony and away from direct judgment or rebuke, makes for a contentious legacy.

For me, that contentiousness – the labor of translating back and forth across paradigms and their preferred conceptual idioms – is where much of the ongoing value continues to reside, in part because it tends to reveal surprising harmonies as often as it does dissensus. So, for instance, while the Marx of the 18th Brumaire encourages us to see conflict and contradiction working crosswise at every social strata, unfolding in real time with byzantine complexity, Foucault asks us to envision a world stratified by forces both vastly conglomerated and infinitesimal, that calcify in structures but also operate beneath their codes, according to rationalities that coexist sometimes smoothly and sometimes uneasily, in fractious multiplicity. That’s only one very generalized example, but it does begin to get at why Marx and Foucault have not seemed to me theorists meaningfully understood as, say, opposites. And, more to the point, they have never seemed less so than right now.

Think, in this vein, of Jasbir Puar’s pathclearing work in her 2017 volume The Right to Maim. There, in the key of anti-imperial critique, she reads Palestine not as some sort of Agambenian state of exception in the global liberal order of things, but as something nearer and more unnerving. It is for her rather a theater of biopolitical experiment, in which control societies test out, through varying styles of life-halting or -inhibiting violence, the modes of regulation proper to racialized surplus populations. Explicitly, The Right to Maim looks to suture the project of biopolitical critique to an acute vision of the political economy of global capital, in an era marked both by precipitously decelerating growth and by an environing climate crisis. We could put it, in compressed terms, like this: If longue duree historians of capital like Giovanni Arrighi are correct, and so too are the climate scientists, then we are speeding toward a moment in which vaster and vaster swaths of the planetary life will be, from the purview of capital and its states, at once negligible as consumers and unassimilable to the swollen ranks of waged labor – will be in this sense surplus – and thus in need of securitized management and optimization. The Right to Maim tells the story of the biopoliticized life of a racialized religious minority, then, as a mapping-out out of future trajectories for imperial liberalism in the season of the Long Downturn: a glimpse, that is, of the shape of power in the world to come.

Perhaps it goes without saying, but I will say it anyway: nothing about this pandemic, with its swaths of laborers and of the institutionally underserved exposed to the probability of death in the name of an economy that must be “open,” seems to me ill-suited to an analytics attending, as Puar’s does, to the interwoven strategies of racist policing, labor discipline, the conjoining of spaces of circulation with those of enforced immobility, the hyper-fetishization of security. One might struggle to imagine a moment in which biopolitics and political economy, as conceptual frameworks, have seemed less agonistically opposed.

Not that this reading of a kind of provisional theoretical comity will be an especially conciliatory note to the guardians of what Brooks calls “campus culture,” for whom one antiliberal – or “postmodernist,” or expert in “grievance” – is basically as good as the next. Certainly it will not be heartening news as far as the tough-talking Creighton, with his withering eye upon the under-productive graduates of “queer or diversity studies,” is concerned. (Creighton who – incidentally! – was in 2019 a journalist in residence at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, where Brooks is of a course a proud alum and board member – proving once again that, for such august institutions, the holy work of neoliberal apologism is long, and never done.) For pundits like these, we professional humanists have only alienation in our flinty hearts, and a dour determination to pass it on to the youth.

And yet, if you’re at all like me, you can’t help sensing something else, something stranger flickering up in these brief and talismanic invocations. These hailings of a figure not really known but conjured, half-seen, evoked in furtive seductions, producing in his wake a kind of malign enchantment… they bring a quick smile, don’t they? It is for all the world as if, against the promptings of reason and sober judgement, they had caught a quick flashing glimpse of the joy in struggle, and in the kinds of being-together it precipitates, and maybe – who can say? – in the possibility of an entire way of life coming into new vitality there. And what they see, or think they see, is a prospect too inviting, too queer, too luminous altogether, not to revile.